One of the greatest filmmakers in history, Martin Scorsese is synonymous with one genre above all others – the gangster movie. Cameron Wolff looks at Scorsese’s most recent in the genre – The Irishman – and explores why Scorsese has the gift when it comes to the mob.

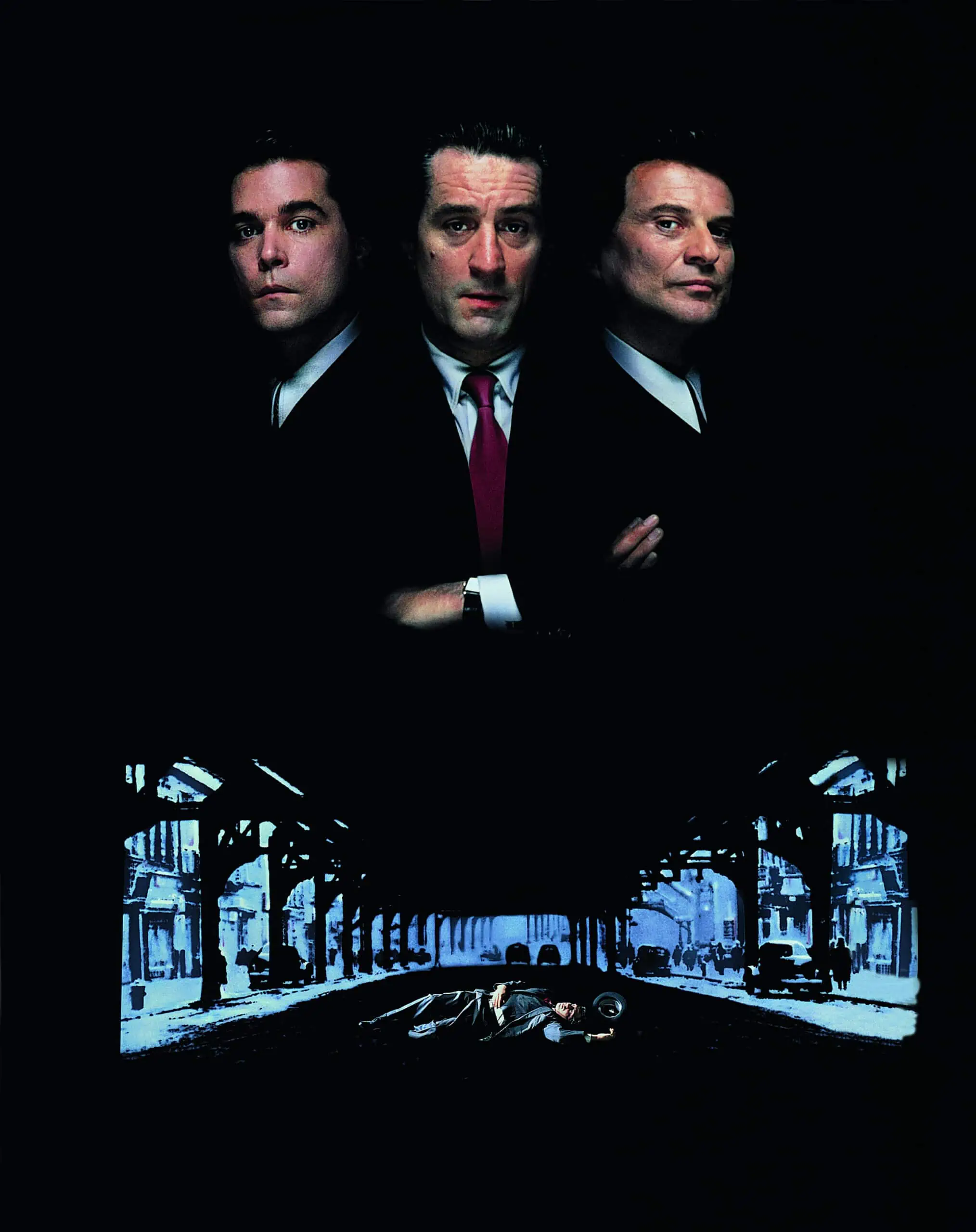

Martin Scorsese understands what the gangster means to America. With films like Goodfellas (1990) and Casino (1995), Scorsese has defined and contributed to the genre as much as any other filmmaker. While it is easy to compare the three films’ similarities and overlapping qualities, each sees Scorsese exploring new ground, looking forward and back in equal measure. 2019’s The Irishman found the director delivering a stunning elegy to ageing and death in the genre in which he forged his reputation as one of Hollywood’s great directors, and we’re exploring that film to see where – and how – Scorsese treads new ground.

“Always Keep Your Mouth Shut” – Narrators Are Never Reliable

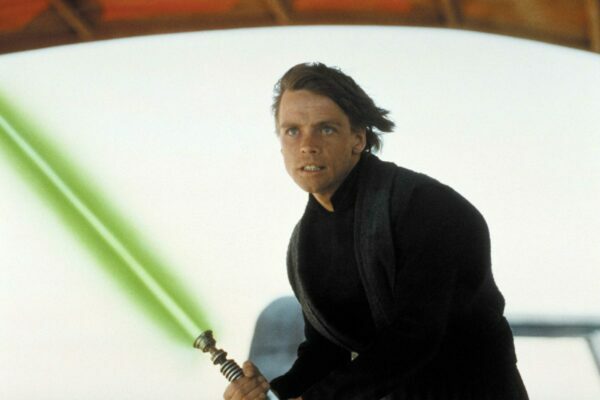

Much like the director himself, the protagonists of Scorsese’s gangster films are often gifted storytellers. Narrators like Goodfellas’ Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) or The Irishman’s Frank Sheeran (Robert DeNiro) tell powerful tales, unflinching in their violent remembrances and unafraid to dig deep into themselves and their actions. All three of the films mentioned here utilize narration in bold ways, letting us experience the world through his character’s words. How can we forget the shock of Nicky’s (Joe Pesci) murder in Casino, a viscerally brutal moment given a poignancy when we realise his narration, an ever-present throughout the film to this point, has suddenly stopped. Scorsese and his co-writers (Nicholas Pileggi on Goodfellas and Casino, Steven Zaillian on The Irishman) always keep these dangerous men at arm’s reach, usually crafting cautionary tales rather than celebrating reprehensible actions. In Goodfellas, Henry Hill is betrayed by Jimmy Conway (Robert DeNiro), pushed out of the world he loves by those more powerful than him. The criminal underworld is depicted as an endless power struggle, where everyone either ends up dead, or on the run.

The criminal underworld is depicted as an endless power struggle, where everyone either ends up dead, or on the run.

“She Knew How to Take Care of People” – Wives and Daughters

In his gangster films, Scorsese pulls multi-faceted performances from a variety of impressive actresses, placing women in powerful positions within a patriarchal lifestyle. Sharon Stone’s portrayal of ex-hustler Ginger in Casino, as well as Lorraine Bracco’s long-suffering mob-wife, Karen, in Goodfellas, depict women deeply indebted to their husbands’ criminal excesses, and yet still attempt to take hold of their situations, with varying degrees of success. In The Irishman, we focus not so much on Sheeran’s wife, but on his daughter, Peggy. In an understated performance of very few words by Anna Paquin, Peggy sits in quiet contemplation of her father, her gaze casting judgement from the point where, as a child, she watches him beat a man on the street. She lacks the bold streak found in Casino’s Ginger, perhaps, but she wields power in a different way. Peggy’s gaze is omnipresent, a constant burden on her father that he must bear for the rest of his life. The women in Scorsese’s gangster films may not carry out the dirty work, but still prove influential forces within their husbands and fathers’ criminal dealings. Love can be fleeting in this world, and the women Scorsese depicts have learned to deal without it.

Frank’s daughter, Peggy, and her bond with Jimmy Hoffa, has an ever-present effect on Frank’s life.

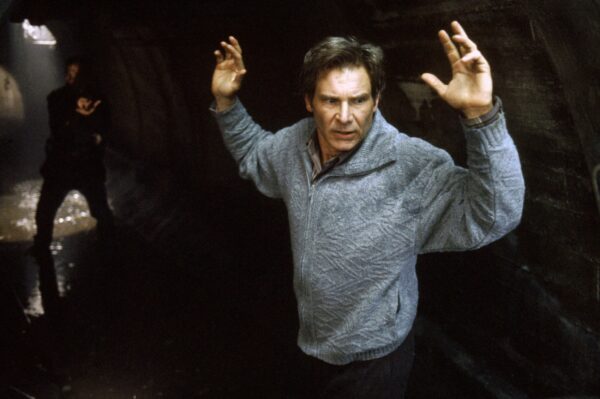

“To Live Any Other Way Was Nuts” – Scorsese switches style

The final hour of The Irishman delivers a sobering – and fitting – finale to a life of crime, as Frank is instructed to murder possibly his only friend, and then left to face old-age alone, mostly abandoned by his family. As the violence erupts, Scorsese maintains a steady distance. When Sheeran murders Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino), the camera is stationary and held away from the action. We witness the process Sheeran perfected over the years, the steady, calculated way he plants his gun on Hoffa’s body and departs without a hitch. All of Frank Sheeran’s closest associates are dead and, in the end, Sheeran only has one last job: to prepare for his own end. As we explore the very last years of Frank’s life, the quick cuts and powerful music cues that accompanied the first act of the movie (and the final acts of Goodfellas and Casino) are gone, replaced by a pervasive tone of melancholy and regret. In a stylistic departure from third acts of Scorsese’s other gangster films, the camera is a quiet observer of what has became a sad, “waiting for God” existence for Frank. Henry Hill and Sam “Ace” Rothstein (De Niro in Casino) were surrounded by death and brutality, but we knew them as young men with little time (or inclination) to dwell on their atrocities. It isn’t hard to see the life Frank Sheeran leads as the logical final step for these men as they reach old age.

The final scene of The Irishman. Frank is full of regret and remorse, as he waits for the end.

“I Remember”: Music and “In the Still of the Night”

The Five Satins’ doo-wop hit, In the Still of the Night, provides a mournful musical motif to The Irishman, guiding us through the events of Frank Sheeran’s life with nostalgic melancholy. Music is essential to all of Scorsese’s films, of course, but In the Still of the Night delivers a particularly unexpected emotional charge. Needle drops in Scorsese’s prior gangster films served as helpful decade-markers or commentary, punctuating big moments with era-relevant (and lyrically-pertinent) music – think Cream’s Sunshine Of Your Love as Jimmy (De Niro) contemplates murder in Goodfellas, or the moment we’re introduced to Tom Cruise’s cocky pool-shark Vincent in The Color Money (1986) – clearing up to the strains of Werewolves Of London by Warren Zevon. Here, in The Irishman, the Five Satins’ classic comes and goes as the soundtrack to Frank Sheeran’s life, and creeps in one last time as the final frame fades to black, and reinforces that Sheeran’s life choices have firmly caught up with him.

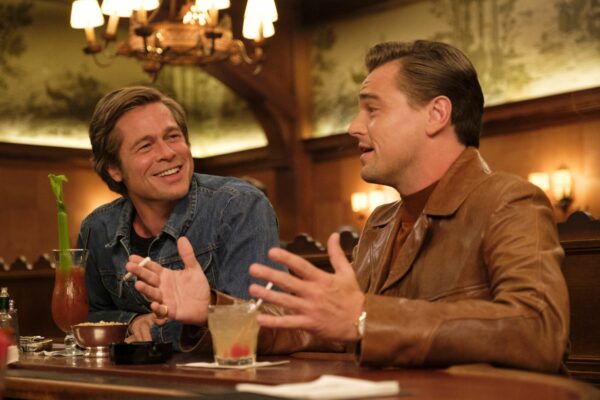

The moment Jimmy Conway decides to murder ball-breaking Maurie in Goodfellas. Scored by Cream.

“I Ain’t Going Nowhere”: Endings

Scorsese’s gangster films often end by following the protagonists beyond their time in the mob. Whether they’re on the run (Goodfellas) or left to grow old in a lonely existence (The Irishman), our ‘hero’ has lost something major, and it isn’t coming back. Perhaps most interestingly of all, the endings of these movies also tend to reflect Scorsese himself, and the point in life at which he finds himself when making the movie. Casino follows Rothstein into middle age (Scorsese was 54 at the time), running bets in quiet San Diego and lamenting the loss of his Atlantic City. Gone are the stakes, replaced by a tourist friendly atmosphere catering to families. Henry Hill also laments the loss of his lifestyle – and freedom – at the end of Goodfellas. Still young, he is sentenced to the suburbs for witness protection, a far cry from the lifestyle he craved as far back as he can remember. We end on former gangsters, living without glory, and haunted by memories of crime and murder. This is where we leave Frank Sheeran at the end of The Irishman. He speaks with a priest in his nursing home, with both men suspecting Sheeran’s soul is beyond saving, his reprehensible acts beyond redemption. The final shot of the film is an homage to Jimmy Hoffa, a door left slightly ajar in remembrance of Frank’s friend, and in anticipation of death itself. Scorsese knows what the gangster means to America, and his success centres around his knowledge, and ability to convey on-screen, what American life means to the gangster.